Introduction#

In this practical we will look at the oxygen reduction reaction. This half-reaction occurs at the cathode of a fuel cell. Fuel cells are used to convert hydrogen gas and oxygen gas into water and energy in hydrogen-powered cars like the Toyota Mirai, for example. However, the oxygen reduction reaction is also interesting as a simple reaction that teaches us a lot about reactions at electrodes in general.

In the oxygen reduction reaction, an oxygen molecule gains four electrons and four protons to form water:

The electrons come from the electrode. The protons come from the electrolyte (we consider an acidic electrolyte here).

The transfer of protons and electrons does not happen all at once; the reaction consists of multiple steps. Although multiple reaction mechanisms are possible, we will look at the simple mechanism from the work of Nørskov et al. [1]. In the first step, an oxygen molecule adsorbs on the surface and dissociates:

Here \(*\) is an empty adsorption site on the surface and \(\mathrm{O^*}\) is an adsorbed oxygen atom. Next, a proton and an electron is transferred to each \(\mathrm{O^*}\):

and this can happen one more time to form water:

Note

Oxygen reduction can also take place through the binding of an entire oxygen molecule [1],

This is particularly relevant for porphyrins [1].

The site \(*\) acts as a catalyst: it binds the intermediates \(\mathrm{O^*}\) and \(\mathrm{HO^*}\) during the reaction. The reduction of oxygen to water causes a flow of electrons: an electric current. The field of science that studies catalytic reactions that drive or require an electric current is called electrocatalysis.

The binding energy in electrocatalysis#

In the lab part, you will find or have found that different catalysts (different electrodes) have a different activity for the oxygen reduction reaction. A major milestone in electrocatalysis was relating the activity of a catalyst to the binding energy to an intermediate.

The binding energies of various oxygen species are related: if a catalyst binds oxygen strongly, it will also bind OH strongly [1, 2].

For optimal catalysis, the catalyst should bind oxygen strongly enough to adsorb it on the surface and enable electron transfer, but not so strongly that the product (water) cannot leave the surface.

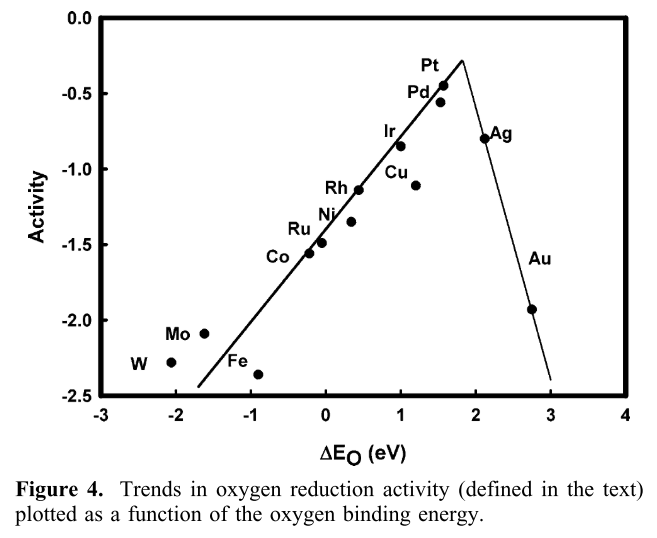

Plotting the activity of various catalysts against their binding energy reveals a ‘volcano plot’: the activity is optimal if the binding energy is not too large, and not too small.

Fig. 2 Volcano plot for the oxygen reduction reaction. Figure taken from Nørskov et al. [1].#

Task for students who model metals: By writing down the Gibbs energy of the reaction for

define the binding energy of an oxygen atom to a metal surface.

Task for students who model porphyrins: By writing down the Gibbs energy of the reaction for

define the binding energy of an oxygen molecule to a porphyrin catalyst.

References#

Jens Kehlet Nørskov, Jan Rossmeisl, Ashildur Logadottir, LRKJ Lindqvist, John R Kitchin, Thomas Bligaard, and Hannes Jonsson. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 108(46):17886–17892, 2004. doi:10.1021/jp047349j.

Bin Lv, Xialiang Li, Kai Guo, Jun Ma, Yanzhi Wang, Haitao Lei, Fang Wang, Xiaotong Jin, Qingxin Zhang, Wei Zhang, and others. Controlling oxygen reduction selectivity through steric effects: electrocatalytic two-electron and four-electron oxygen reduction with cobalt porphyrin atropisomers. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 60(23):12742–12746, 2021. doi:10.1002/anie.202102523.

Ambarish Kulkarni, Samira Siahrostami, Anjli Patel, and Jens K Nørskov. Understanding catalytic activity trends in the oxygen reduction reaction. Chemical reviews, 118(5):2302–2312, 2018. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00488.